Inside the Global Web of Antiquities Smuggling: How Stolen Artifacts Fuel Crime and Erase History. Uncover the Networks, Motives, and Consequences Behind the Illicit Trade.

- Introduction: The Scope and Scale of Antiquities Smuggling

- Historical Context: How the Trade in Stolen Artifacts Began

- Key Smuggling Routes and Hotspots

- The Role of Organized Crime and Corrupt Officials

- Methods of Smuggling and Concealment

- Impact on Source Countries and Cultural Heritage

- International Laws and Enforcement Challenges

- Case Studies: Notorious Smuggling Rings and Recovered Treasures

- The Art Market: Auction Houses, Dealers, and Buyers

- Efforts in Prevention and Repatriation

- Conclusion: The Ongoing Battle to Protect the World’s Heritage

- Sources & References

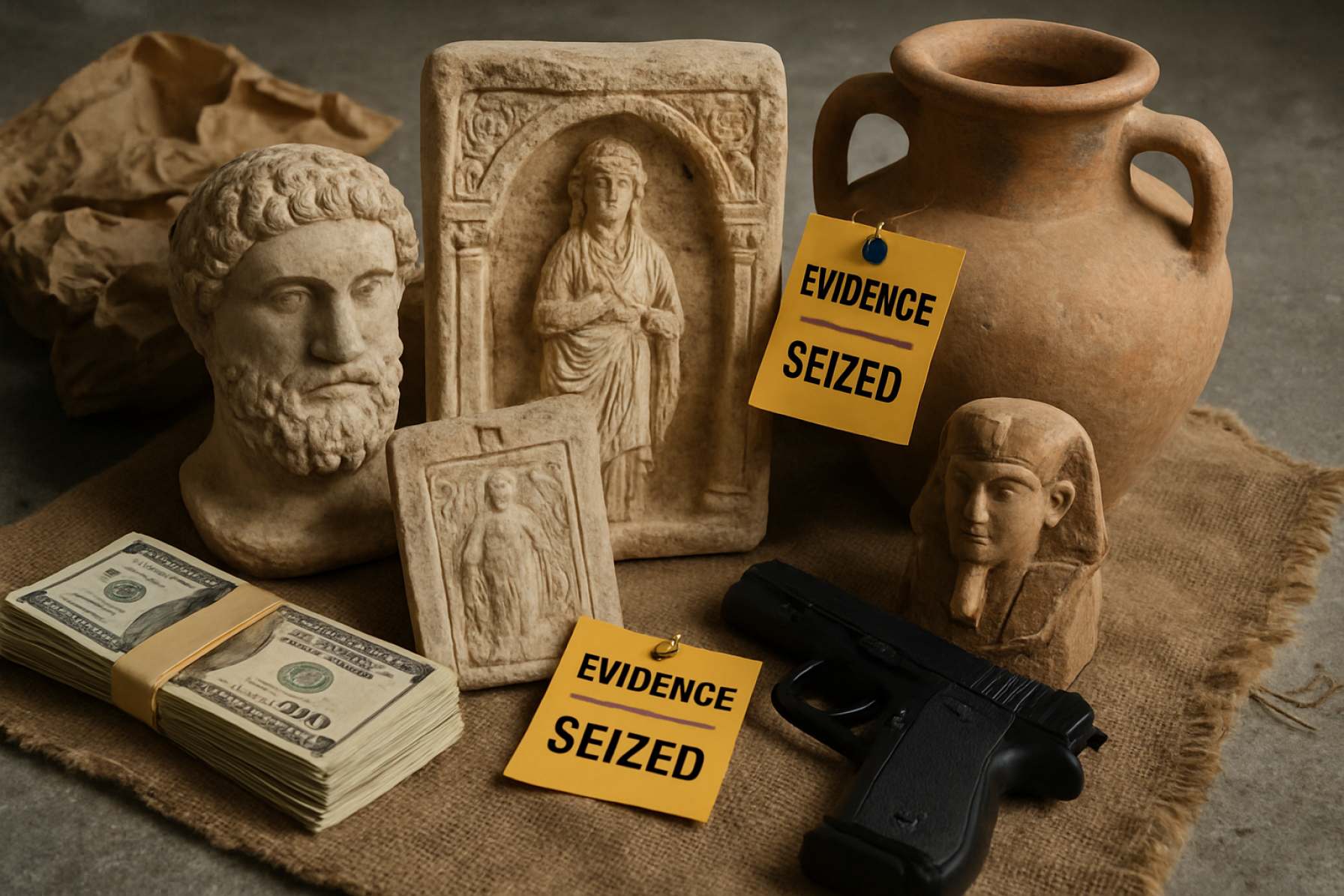

Introduction: The Scope and Scale of Antiquities Smuggling

Antiquities smuggling refers to the illicit trade, transport, and sale of cultural artifacts, often stolen or illegally excavated from archaeological sites. This black market industry has grown into a multi-billion-dollar global enterprise, driven by high demand from private collectors, museums, and galleries. The scope of antiquities smuggling is vast, affecting countries across the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where rich archaeological heritage is particularly vulnerable to looting and trafficking. The scale of the problem is difficult to quantify due to the clandestine nature of the trade, but estimates suggest that billions of dollars’ worth of cultural property are trafficked annually, with proceeds often funding organized crime and, in some cases, terrorist groups United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

The impact of antiquities smuggling extends beyond financial loss; it erases historical context, undermines academic research, and deprives communities of their cultural heritage. The destruction of archaeological sites during illegal excavations results in the permanent loss of invaluable information about past civilizations. International efforts to combat this crime include conventions, such as the 1970 UNESCO Convention, and coordinated law enforcement actions, yet enforcement remains challenging due to porous borders, limited resources, and the involvement of sophisticated criminal networks UNESCO. As the market for illicit antiquities continues to evolve, so too must the strategies for detection, prevention, and restitution, making antiquities smuggling a persistent and complex global issue.

Historical Context: How the Trade in Stolen Artifacts Began

The illicit trade in antiquities has deep historical roots, evolving alongside the development of archaeology and the global art market. While the removal of cultural objects dates back to ancient times—such as Roman looting of Greek art—the modern phenomenon of antiquities smuggling accelerated during the colonial era. European powers, driven by a fascination with the ancient world, often removed artifacts from colonized regions under the guise of scientific exploration or preservation. This practice was institutionalized through the activities of museums and private collectors, who sought to amass prestigious collections, sometimes disregarding the legal or ethical implications of their acquisitions (The British Museum).

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw a surge in archaeological excavations, often conducted with little oversight in countries such as Egypt, Iraq, and Greece. The lack of robust legal frameworks enabled the widespread removal and export of artifacts. As national identities strengthened and post-colonial states emerged, source countries began to enact stricter laws to protect their heritage. However, the demand for antiquities in Western markets continued to fuel smuggling networks, often involving local looters, middlemen, and international dealers (UNESCO).

The persistence of antiquities smuggling is thus rooted in a complex interplay of historical power dynamics, evolving legal standards, and enduring market demand. Understanding this context is essential for addressing the ongoing challenges of cultural heritage protection and the ethical responsibilities of collectors and institutions.

Key Smuggling Routes and Hotspots

Antiquities smuggling is a transnational crime that exploits regions rich in cultural heritage but often plagued by conflict, weak governance, or economic instability. Key smuggling routes and hotspots have emerged in response to both the supply of illicit artifacts and the demand from international markets. The Middle East, particularly countries like Syria, Iraq, and Egypt, remains a primary source of trafficked antiquities due to ongoing conflict and the presence of significant archaeological sites. Looted items are often transported through neighboring countries such as Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, which serve as transit points before artifacts reach Europe or North America United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Southeast Asia is another hotspot, with Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar frequently targeted for their ancient temples and artifacts. Smugglers use porous borders and clandestine networks to move items to major hubs like Bangkok and Singapore, from where they are shipped to collectors and auction houses worldwide UNESCO. In Latin America, Peru, Mexico, and Guatemala are notable for the looting of pre-Columbian artifacts, which are often smuggled through Central America to the United States.

These routes are facilitated by a combination of local looters, organized crime syndicates, and complicit dealers. The use of online platforms has further complicated enforcement, allowing traffickers to reach buyers directly and obscure the origins of artifacts. International cooperation and targeted enforcement along these key routes remain critical to disrupting the illicit trade in antiquities INTERPOL.

The Role of Organized Crime and Corrupt Officials

The illicit trade in antiquities is deeply intertwined with the operations of organized crime networks and the complicity of corrupt officials. Organized crime groups exploit the high value and relative portability of cultural artifacts, orchestrating sophisticated smuggling operations that span continents. These networks often collaborate with local looters, providing them with resources and logistical support to extract artifacts from archaeological sites, which are then funneled through a series of intermediaries to obscure their origins. The involvement of organized crime not only increases the scale and efficiency of antiquities smuggling but also introduces violence and intimidation into the process, further endangering cultural heritage and local communities.

Corrupt officials play a pivotal role in facilitating the movement of illicit antiquities. They may provide false documentation, overlook illegal excavations, or enable the passage of smuggled goods through customs checkpoints. In some cases, officials are directly involved in the trafficking networks, leveraging their positions to profit from the trade. The complicity of authorities undermines law enforcement efforts and perpetuates a cycle of impunity, making it exceedingly difficult to disrupt the flow of stolen artifacts. International organizations such as INTERPOL and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime have highlighted the need for stronger governance, transparency, and cross-border cooperation to combat the influence of organized crime and corruption in antiquities smuggling.

Methods of Smuggling and Concealment

Antiquities smugglers employ a range of sophisticated methods to evade detection and transport illicit artifacts across borders. One common technique involves the falsification of provenance documents, which are used to legitimize the origins of stolen or illegally excavated items. Smugglers may also mislabel shipments, declaring valuable antiquities as mundane goods such as ceramics or construction materials to avoid scrutiny during customs inspections. In some cases, artifacts are disassembled or fragmented, making them easier to hide within legitimate cargo or personal luggage, only to be reassembled once they reach their destination.

Concealment strategies often exploit the complexity of international shipping routes. Smugglers may use transit countries with lax customs enforcement or limited cultural property regulations as waypoints, obscuring the true origin and destination of the artifacts. Additionally, the use of freeports—secure storage facilities in international trade zones—allows traffickers to store and trade antiquities with minimal oversight, further complicating law enforcement efforts. The rise of online marketplaces and social media platforms has also facilitated the discreet sale and movement of illicit antiquities, with transactions often conducted using encrypted communications and digital currencies to mask the identities of buyers and sellers.

Law enforcement agencies, such as INTERPOL and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, have documented these evolving smuggling tactics and continue to adapt their investigative techniques in response. Despite these efforts, the ingenuity and adaptability of smugglers present ongoing challenges to the protection of cultural heritage worldwide.

Impact on Source Countries and Cultural Heritage

Antiquities smuggling has profound and often irreversible consequences for source countries and their cultural heritage. The illicit removal of artifacts from archaeological sites not only strips nations of their tangible history but also erodes the intangible connections communities have with their past. When objects are trafficked abroad, they are frequently divorced from their original context, making it difficult or impossible for scholars to reconstruct historical narratives or understand the full significance of the items. This loss of context diminishes the educational and cultural value of the artifacts, undermining national identity and pride.

Economically, source countries suffer as well. The destruction and looting of sites can deter tourism, a vital source of revenue for many nations with rich archaeological legacies. Furthermore, the costs associated with protecting sites, investigating thefts, and pursuing repatriation claims place additional burdens on already limited resources. The illicit trade also fuels corruption and organized crime, destabilizing local communities and undermining the rule of law.

International organizations such as UNESCO and INTERPOL have highlighted the devastating impact of antiquities smuggling, emphasizing the need for stronger legal frameworks and international cooperation. Despite these efforts, the demand for rare and valuable artifacts continues to incentivize looting, making the protection of cultural heritage an ongoing challenge for source countries worldwide.

International Laws and Enforcement Challenges

International efforts to combat antiquities smuggling are anchored in a patchwork of treaties, conventions, and bilateral agreements. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 1970 Convention is the cornerstone, obligating signatory states to prevent the illicit import, export, and transfer of ownership of cultural property. Complementing this, the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT) 1995 Convention addresses private law aspects, such as restitution and return of stolen or illegally exported cultural objects. Despite these frameworks, enforcement remains fraught with challenges.

Jurisdictional limitations are a primary obstacle. Antiquities often transit through multiple countries, exploiting legal loopholes and inconsistent national laws. Many source countries lack the resources or political will to enforce existing regulations, while market countries may have less stringent import controls. The clandestine nature of smuggling networks, often intertwined with organized crime, further complicates detection and prosecution. Even when objects are identified, proving provenance and ownership can be arduous, especially for items lacking documentation or those looted from conflict zones.

International cooperation is essential but often hampered by diplomatic sensitivities and differing legal standards. Agencies such as INTERPOL and Europol facilitate information sharing and joint operations, but their mandates are limited. Ultimately, the effectiveness of international law depends on harmonized legislation, robust enforcement mechanisms, and sustained political commitment across borders.

Case Studies: Notorious Smuggling Rings and Recovered Treasures

The global trade in illicit antiquities has been shaped by several high-profile smuggling rings whose operations have spanned continents and decades. One of the most notorious was the network led by Italian art dealer Gianfranco Becchina, whose activities were exposed in the early 2000s. Becchina’s ring trafficked thousands of looted artifacts from Italy to major museums and private collectors worldwide, often using forged provenance documents to legitimize the items. The investigation, known as Operation Geryon, resulted in the seizure of over 6,000 artifacts and the repatriation of significant pieces to Italy, including Etruscan vases and Roman sculptures (Carabinieri TPC).

Another infamous case involved Subhash Kapoor, a New York-based dealer whose “Art of the Past” gallery served as a front for smuggling South Asian antiquities. Kapoor’s network sourced stolen temple idols and sculptures from India, laundering them through a complex web of intermediaries. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security and Indian authorities collaborated to recover hundreds of artifacts, including the celebrated bronze Nataraja statue, which was returned to India in 2014 (U.S. Department of Homeland Security).

These cases underscore the sophistication of smuggling operations and the importance of international cooperation in recovering cultural heritage. The successful repatriation of treasures not only restores national patrimony but also serves as a deterrent to future trafficking, highlighting the ongoing efforts of law enforcement and cultural agencies worldwide.

The Art Market: Auction Houses, Dealers, and Buyers

The art market—comprising auction houses, private dealers, and collectors—plays a pivotal role in the circulation of antiquities, both licit and illicit. Auction houses such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s have faced scrutiny for inadvertently selling looted artifacts, sometimes due to insufficient provenance checks or reliance on forged documentation. Dealers, operating in both formal galleries and informal networks, often act as intermediaries, facilitating the movement of antiquities from source countries to buyers worldwide. The opacity of private sales and the use of freeports—tax-free storage facilities—further complicate efforts to trace the origins of objects and enforce legal and ethical standards.

Buyers, ranging from private collectors to major museums, may unwittingly or knowingly acquire smuggled antiquities. The demand for rare and prestigious objects incentivizes looters and traffickers, perpetuating a cycle of cultural loss in source countries. While international agreements such as the UNESCO 1970 Convention and national laws have established frameworks for due diligence and repatriation, enforcement remains inconsistent. Recent high-profile restitutions, such as the return of looted artifacts by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, highlight both the scale of the problem and the growing pressure on market participants to adopt stricter ethical standards.

Ultimately, the art market’s structure—characterized by confidentiality, fragmented regulation, and global reach—creates vulnerabilities that traffickers exploit. Addressing antiquities smuggling requires coordinated action among auction houses, dealers, buyers, and authorities to improve transparency, provenance research, and compliance with international norms.

Efforts in Prevention and Repatriation

Efforts to prevent antiquities smuggling and facilitate the repatriation of looted artifacts have intensified over recent decades, involving a combination of international cooperation, legal frameworks, and technological advancements. International conventions, such as the UNESCO Convention of 1970, provide a legal basis for member states to prohibit and prevent the illicit import, export, and transfer of cultural property. Many countries have enacted stricter national laws and established specialized law enforcement units to monitor borders, investigate trafficking networks, and recover stolen items.

Repatriation efforts are often the result of diplomatic negotiations and legal proceedings. High-profile cases, such as the return of the Euphronios Krater to Italy, highlight the importance of provenance research and international collaboration. Organizations like INTERPOL and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime maintain databases of stolen artifacts and provide training to law enforcement agencies worldwide. Additionally, museums and auction houses are increasingly adopting due diligence protocols to verify the origins of items before acquisition or sale.

Technological tools, such as digital registries, satellite imagery, and blockchain, are being leveraged to track artifacts and monitor vulnerable archaeological sites. Public awareness campaigns and community engagement also play a crucial role in deterring looting and encouraging the reporting of suspicious activities. Despite these efforts, challenges remain due to the high demand for antiquities, the complexity of international law, and the clandestine nature of smuggling networks.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Battle to Protect the World's Heritage

The ongoing battle against antiquities smuggling remains a complex and urgent challenge for the global community. Despite increased awareness and international cooperation, the illicit trade in cultural artifacts continues to threaten the preservation of humanity’s shared heritage. Smugglers exploit conflict zones, weak legal frameworks, and the high demand from private collectors and institutions, making the fight against this crime both multifaceted and persistent. Efforts by organizations such as UNESCO and INTERPOL have led to the development of international conventions, databases, and coordinated law enforcement actions, yet the scale of the problem remains daunting.

Recent high-profile repatriations and prosecutions demonstrate progress, but also highlight the adaptability of smuggling networks. The digital age has introduced new challenges, with online marketplaces facilitating the rapid and often anonymous sale of looted artifacts. Addressing these issues requires not only robust legal measures and cross-border collaboration, but also public education and the involvement of the art market in due diligence practices. Ultimately, the protection of the world’s heritage depends on sustained vigilance, international solidarity, and a shared commitment to valuing cultural legacy over profit. As long as demand persists and enforcement gaps remain, the struggle to safeguard antiquities will continue, underscoring the need for ongoing innovation and cooperation in this critical field.

Sources & References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- UNESCO

- UNESCO

- International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT)

- Europol

- Carabinieri TPC

- Christie’s

- Sotheby’s

- Metropolitan Museum of Art